|

|

N

E W S |

New Collectibles •05/25 - NECA Sesame Street: Count Von Count Ultimate Action Figure

•04/25 - Reaction Sesame Street: Big Bird and Snuffy •03/25 - NECA Sesame Street: Ernie Ultimate Action Figure, Bert Ultimate Action Figure

•03/25 - Boss Studios Fraggle Rock: Boober Action Figure, Wembley Action Figure, Mokey Action Figure, Sprocket Action Figure •08/24 - Reaction Sesame Street: Big Bird, Mr. Hooper, Sherlock Hemlock, Super Grover |

||

|

|

|

Jokes Kermit wouldn't dare say The Jim Henson Company is moving in a new direction with Puppet Up. A special will air November 20 and TBS has ordered 30 episodes of Puppet Up for TBS broadband. A late night talk show is also in the works. Courtesy

of The New York Times For one thing, the puppeteers weren’t hidden. They performed in full view, with their puppets held over their heads for a camera to capture and project to television monitors next to the stage. And instead of following a script, the Henson troupe improvised skits, with audience members encouraged to chime in their own story ideas.

This being a comedy club, those ideas weren’t exactly what the Henson Company might have used on “The Muppet Show” or “Sesame Street.” Asked to suggest a career for a skit about a job interview, one audience member proposed proctology; the performance featured a large gorilla puppet re-enacting the kind of painful probes common in that medical specialty. Who would have thought that the company that introduced the phrase “It’s not easy being green” would be working blue? It’s just one of the ways a production company known for beloved child-friendly franchises is trying to find a new creative spark.

He is making progress. TBS is taping a Henson improv performance scheduled for Wednesday at the Comedy Festival in Las Vegas, and will show it as an hourlong special titled “Puppet Up! Uncensored” on Nov. 20. In addition TBS has ordered 30 episodes of "Uncensored" for its coming broadband channel. The network is also considering a semi-improvisational late-night talk show in which everyone is a puppet except for the human celebrity guests. Another project the Henson Company is shopping around is “Tinseltown,” concerning a gay puppet couple balancing work in Hollywood with life as parents of an adopted human son. In the five-minute presentation tape for “Tinseltown,” Bobby is a margarita-swilling pig with a raspy lisp, and his partner is a bull named Samson. When their sullen 12-year-old son plucks a beer from the refrigerator, Bobby dismisses Samson’s concern, telling him, “Oh, it was a light beer.” With its new adult direction, the company is latching onto a cable trend. MTV2’s “Wonder Showzen” has made ample use of the genre, and the channel is also bringing back the puppet pranksters of “Crank Yankers,” which originally ran on Comedy Central. IFC has revived “Greg the Bunny” to parody popular films, and next year Starz is importing a different racy rabbit, “The Bronx Bunny,” from British television.

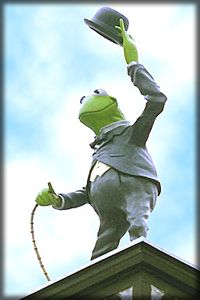

The Henson Company has been at this address since 2000, the latest tenant in the bungalows Charlie Chaplin built for his own studio in 1917. The current occupants pay tribute to him at the central gate with a statue of Kermit the Frog dressed in Chaplin’s signature bowler and cane. But Kermit is no longer a priority for Mr. Henson since he sold the rights to the Muppets franchise to the Walt Disney Company in 2004. While Disney is likely to call on the Henson Company to produce future incarnations of the Muppets, their corporate adoption has freed Mr. Henson to focus on creating new characters that could become franchises in their own right.

His company remains active in other children’s properties — like development of a feature-film adaptation of its 1980s show “Fraggle Rock” — and is also interested in coming up with the kind of production that appeals to all ages, as its syndicated variety series “The Muppet Show” did on CBS stations from 1976 to 1981. There were several attempts in the 1980s and 1990s to recapture that magic, with mixed results. That’s when the notion that improvised comedy could be a source of creative resurgence arose. “One thing that occurred to me in the last few years was that that spark wasn’t there anymore and that we were really sticking to the script,” Mr. Henson said. Improv was also something of a necessity: the company was having difficulty attracting writers to dream up puppet-based material. Mr. Henson also wanted to see his puppeteers ad-libbing more, the way the earlier generation that gave voice to “The Muppet Show” often did.

It was that kind of impromptu performance that Mr. Henson said was essential to recovering the company’s voice. He turned to Patrick Bristow, an actor and instructor at the Los Angeles improv company the Groundlings, for help a few years ago. Though initially dubious that puppetry and improv could be married, Mr. Bristow began teaching the puppeteers how to string together stories on the fly from audience suggestions. Paying attention to the motions of a puppet while clearing the mind for free-associative creativity is not for the faint at heart, Mr. Bristow discovered. As he described the practice, “it’s like parts of the brain that never spoke to each other are screaming, ‘Hey! Over here!’ ”

The first few weeks of training were difficult, Mr. Bristow remembered, and one discouraged puppeteer even dropped out. Puppetry doesn’t exactly lend itself to improvisation, which traditionally emphasizes eye contact between the performers. The Henson puppeteers have to stare at monitors on the floor in order to see their puppets move; their brand of improvisation forces them to listen intently. “At first it was pretty challenging, to say the least,” Ms. Buescher recalled. In time Mr. Bristow felt they were ready for a performance. When Mr. Henson recommended his lot’s soundstage, Mr. Bristow had little idea that it would not be an intimate gathering. “They rented bleachers and served wine, cheese and crackers,” Mr. Bristow remembered. “No pressure or anything.” The crowd included a representative from the U.S. Comedy Arts Festival, who invited the puppeteers to perform in March in Aspen, Colo.

Improvisation has also helped the staff mold the identity of puppets from scratch. Ms. Buescher began taking a liking to a diapered pug she named Piddles. The puppet displays an impish charm and, on occasion, uncontrollable gas. “Eventually you fall in love with one of them, and you make them your own,” she said. “I love Piddles. She’s so innocent but so filthy and dark.” Those aren’t exactly the adjectives that come to mind in describing the legacy of Jim Henson, who died in 1990. But his son said that the company’s success in family-friendly entertainment had obscured Jim Henson’s more irreverent work earlier in his career. In the 1960s Jim Henson’s puppet humor included the occasional sexual innuendo and drug references; his creations were even featured on the first season of “Saturday Night Live.”

But while the father’s earlier work may have foreshadowed the son’s new direction, Mr. Henson emphasized that being offensive was not the point. “We didn’t set out to do risqué adult-exclusive content,” he said. “What we did set out to do is to forget all the rules of the 8 p.m. sensibility, what puppets do that aren’t in preschool, and instead let’s just do what we as puppeteers think is the funniest thing we can do in the moment.”

|

|

|

|

home | news | collectibles | articles | forum | guides | radio | cards | help

Fan site Muppet Central created by Phillip Chapman. Updates by Muppet

Central Staff. All Muppets, Bear

Muppet Central exists to unite fans of the Muppets around the world. |

Brian

Henson — co-chief executive, with his sister, Lisa Henson,

and a puppeteer at the company his father founded — wants

to restore the company’s past glory. “We lost our position

as funny, popular entertainment in the prime-time arena, so I’m

trying to get back there,” he said. “To do that and

be innovative, we have to really establish a new voice.”

Brian

Henson — co-chief executive, with his sister, Lisa Henson,

and a puppeteer at the company his father founded — wants

to restore the company’s past glory. “We lost our position

as funny, popular entertainment in the prime-time arena, so I’m

trying to get back there,” he said. “To do that and

be innovative, we have to really establish a new voice.” Back

at Henson the multiple projects make for a busy time at its headquarters,

a five-acre lot in Hollywood that doesn’t quite fit in with

the seedier elements of the neighborhood, just south of Sunset Boulevard.

Inside a converted farmhouse on the grounds, an employee creates

a new female character, Gina Cappellini, meant for one of the resident

puppeteers, Julianne Buescher, who slides the puppet-in-progress

over her hand. Gina’s eyes have yet to be glued on; they’re

still trying to perfect her sloe-eyed expression with the help of

an Angelina Jolie photo pinned to the wall.

Back

at Henson the multiple projects make for a busy time at its headquarters,

a five-acre lot in Hollywood that doesn’t quite fit in with

the seedier elements of the neighborhood, just south of Sunset Boulevard.

Inside a converted farmhouse on the grounds, an employee creates

a new female character, Gina Cappellini, meant for one of the resident

puppeteers, Julianne Buescher, who slides the puppet-in-progress

over her hand. Gina’s eyes have yet to be glued on; they’re

still trying to perfect her sloe-eyed expression with the help of

an Angelina Jolie photo pinned to the wall. “It’s

liberated me from needing to service that because having the Muppets

becomes a big, big deal,” Mr. Henson said. “It’s

consumer products, it’s publishing, all that stuff.”

“It’s

liberated me from needing to service that because having the Muppets

becomes a big, big deal,” Mr. Henson said. “It’s

consumer products, it’s publishing, all that stuff.” The

current corps was in agreement that sometimes the funniest scenes

occurred off camera. Bill Barretta, a puppeteer who has worked closely

with Mr. Henson for 15 years, recalled cracking up people on the

set between takes. “We’d cut from a scene, and I’d

make it so my character had way too much to drink, and he’d

start cursing at the crew,” Mr. Barretta said. “It would

break up the tension and remind us that we’re there to have

fun.”

The

current corps was in agreement that sometimes the funniest scenes

occurred off camera. Bill Barretta, a puppeteer who has worked closely

with Mr. Henson for 15 years, recalled cracking up people on the

set between takes. “We’d cut from a scene, and I’d

make it so my character had way too much to drink, and he’d

start cursing at the crew,” Mr. Barretta said. “It would

break up the tension and remind us that we’re there to have

fun.”

“Because

of ‘Sesame Street’ people thought of him as a children’s

performer,” Brian Henson said. “It was sort of odd for

him because he was until then an adult performer.”

“Because

of ‘Sesame Street’ people thought of him as a children’s

performer,” Brian Henson said. “It was sort of odd for

him because he was until then an adult performer.”