- Joined

- Apr 11, 2002

- Messages

- 8,293

- Reaction score

- 3,425

Banjo's Place in US History Lauded

Coutesy of the Associated Press

Banjos have bounced on the knees of slaves and mountain folk, leaned in the corners of Boston mansions and stolen the stages of music halls.

But the humble banjo, which evolved from its African roots to become 19th-century America's most popular instrument, strummed its way right out of the musical mainstream.

An exhibit called "The Banjo: The People and the Sounds of America's Instrument," on view at the National Heritage Museum in Lexington through Sept. 3, seeks to restore "America's instrument" to its rightful place.

"There's a lot of different stories to be told. It's one of the few really American instruments," said Jim Bollman, a collector who donated many of the instruments in the Lexington exhibit.

That's not to say the banjo has strummed its last chords. After all, it remains a main ingredient in folk and bluegrass music, and the instrument sees periodic revivals, such in the jaw-dropping success of the "O Brother, Where Art Thou?" soundtrack, which won this year's Grammy for album of the year.

More than 60 banjos are on show in the exhibit, including an akonting — the banjo's predecessor from Gambia. There also are ornate "presentation banjos" made of cherry, mahogany and rosewood — even whalebone — inlaid with mother-of-pearl floral patterns, and silver- and gold-plated strings.

Other instruments range from a Henry P. Stichter banjo made in 1847 to a brand-new Deering "Crossfire" solid-body banjo. More than 50 of them come from Bollman's personal collection; some would fetch in the tens of thousands of dollars.

There are also displays of sheet music, lithographs, pottery and posters featuring the instruments, including William Sydney Mount's 1865 painting, "The Banjo Player." And the exhibit features items that demonstrate the role of minstrel shows, with their crass and cruel characterizations of blacks, that were so much a part of the instrument's history.

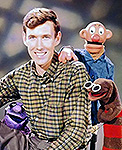

Bela Fleck's Grammy is on view, and there's also a poster of Kermit the Frog with a banjo on his knee in "The Muppet Movie."

Over the years, the banjo's down-home strains have largely become associated with whimsy and folklore, and even a sense of the corny, said Phyllis Barney, executive director of the North American Folk Music and Dance Alliance in Silver Spring, Md.

"If you want to evoke a feeling of home or country, you just need a couple of bars of the banjo, and if you have your eyes closed, you're looking across a wheat field," she said.

It is believed that the banjo's predecessor was the akonting, a Gambian instrument fashioned from gourds and animal hides that came to America with slaves.

It was largely an instrument of Southern blacks in the early 1800s, and was rarely seen in the North. It was an every man's instrument that even the poorest porch musician could afford.

"You could make a banjo out of a dead groundhog and a coffee can and a few sticks of wood and some stove bolts, and they regularly did that in the South," Bollman said.

But the impatient banjo didn't stay South. It became a favorite prop of minstrel shows — white actors who wore blackface and used stereotypes to parody blacks — that traveled north and west with circuses. "It's kind of an icon for minstrelsy, and by extension racism and bigotry," Bollman said.

The shows became enormously popular. By the 1860s, some 160 minstrel companies played to huge crowds around the nation, introducing the country to the worst stereotypes of blacks, but also to black spirituals and songs, as well as Irish ballads, German folk songs and opera.

Minstrel shows also introduced the instrument to whites. Its infectious strains sparked campus banjo clubs, concert hall performances and parlor gatherings among the more affluent.

"When you want genuine music — music that will come right home to you like a bad quarter, suffuse your system like strychnine whisky ... just smash your piano, and invoke the glory-beaming banjo!" Mark Twain quipped in 1865.

The new popularity also meant a booming market. Hundreds of patents were issued for improvements, and instrument makers, including A.C. Fairbanks, William A. Cole and Bay State in Boston, began manufacturing "presentation banjos" for the wealthy.

At the Heritage Museum show, Eugene and Gywnne McKenzie, of Memphis, Tenn., lingered over the presentation banjos made to please the ears and the eyes.

"They're so beautiful," said Gwynne McKenzie, 66. "I think they put the art in it not so that it would be displayed, but because they wanted to play a beautiful instrument."

As jazz guitar slowly edged out the banjo in popular music, its fortunes faded, and the Depression knocked the banjo out of the hands of common folks.

"People didn't need them, and they weren't crucial to living for someone to get through the day, just like lots of other excesses," Bollman said.

Today, the banjo maintains an important spot in American music tradition, but is rarely heard on the airwaves. Traditional music enthusiasts were all the more dumbfounded by the success of "O Brother, Where Art Thou?" — so much so that folk groups held a "Roots Music Industry Summit" in Nashville last month.

"There is a real need to get away from being spoon-fed your entertainment, so music buyers are more interested in digging a little deeper" into traditional American music, Barney said.

Coutesy of the Associated Press

Banjos have bounced on the knees of slaves and mountain folk, leaned in the corners of Boston mansions and stolen the stages of music halls.

But the humble banjo, which evolved from its African roots to become 19th-century America's most popular instrument, strummed its way right out of the musical mainstream.

An exhibit called "The Banjo: The People and the Sounds of America's Instrument," on view at the National Heritage Museum in Lexington through Sept. 3, seeks to restore "America's instrument" to its rightful place.

"There's a lot of different stories to be told. It's one of the few really American instruments," said Jim Bollman, a collector who donated many of the instruments in the Lexington exhibit.

That's not to say the banjo has strummed its last chords. After all, it remains a main ingredient in folk and bluegrass music, and the instrument sees periodic revivals, such in the jaw-dropping success of the "O Brother, Where Art Thou?" soundtrack, which won this year's Grammy for album of the year.

More than 60 banjos are on show in the exhibit, including an akonting — the banjo's predecessor from Gambia. There also are ornate "presentation banjos" made of cherry, mahogany and rosewood — even whalebone — inlaid with mother-of-pearl floral patterns, and silver- and gold-plated strings.

Other instruments range from a Henry P. Stichter banjo made in 1847 to a brand-new Deering "Crossfire" solid-body banjo. More than 50 of them come from Bollman's personal collection; some would fetch in the tens of thousands of dollars.

There are also displays of sheet music, lithographs, pottery and posters featuring the instruments, including William Sydney Mount's 1865 painting, "The Banjo Player." And the exhibit features items that demonstrate the role of minstrel shows, with their crass and cruel characterizations of blacks, that were so much a part of the instrument's history.

Bela Fleck's Grammy is on view, and there's also a poster of Kermit the Frog with a banjo on his knee in "The Muppet Movie."

Over the years, the banjo's down-home strains have largely become associated with whimsy and folklore, and even a sense of the corny, said Phyllis Barney, executive director of the North American Folk Music and Dance Alliance in Silver Spring, Md.

"If you want to evoke a feeling of home or country, you just need a couple of bars of the banjo, and if you have your eyes closed, you're looking across a wheat field," she said.

It is believed that the banjo's predecessor was the akonting, a Gambian instrument fashioned from gourds and animal hides that came to America with slaves.

It was largely an instrument of Southern blacks in the early 1800s, and was rarely seen in the North. It was an every man's instrument that even the poorest porch musician could afford.

"You could make a banjo out of a dead groundhog and a coffee can and a few sticks of wood and some stove bolts, and they regularly did that in the South," Bollman said.

But the impatient banjo didn't stay South. It became a favorite prop of minstrel shows — white actors who wore blackface and used stereotypes to parody blacks — that traveled north and west with circuses. "It's kind of an icon for minstrelsy, and by extension racism and bigotry," Bollman said.

The shows became enormously popular. By the 1860s, some 160 minstrel companies played to huge crowds around the nation, introducing the country to the worst stereotypes of blacks, but also to black spirituals and songs, as well as Irish ballads, German folk songs and opera.

Minstrel shows also introduced the instrument to whites. Its infectious strains sparked campus banjo clubs, concert hall performances and parlor gatherings among the more affluent.

"When you want genuine music — music that will come right home to you like a bad quarter, suffuse your system like strychnine whisky ... just smash your piano, and invoke the glory-beaming banjo!" Mark Twain quipped in 1865.

The new popularity also meant a booming market. Hundreds of patents were issued for improvements, and instrument makers, including A.C. Fairbanks, William A. Cole and Bay State in Boston, began manufacturing "presentation banjos" for the wealthy.

At the Heritage Museum show, Eugene and Gywnne McKenzie, of Memphis, Tenn., lingered over the presentation banjos made to please the ears and the eyes.

"They're so beautiful," said Gwynne McKenzie, 66. "I think they put the art in it not so that it would be displayed, but because they wanted to play a beautiful instrument."

As jazz guitar slowly edged out the banjo in popular music, its fortunes faded, and the Depression knocked the banjo out of the hands of common folks.

"People didn't need them, and they weren't crucial to living for someone to get through the day, just like lots of other excesses," Bollman said.

Today, the banjo maintains an important spot in American music tradition, but is rarely heard on the airwaves. Traditional music enthusiasts were all the more dumbfounded by the success of "O Brother, Where Art Thou?" — so much so that folk groups held a "Roots Music Industry Summit" in Nashville last month.

"There is a real need to get away from being spoon-fed your entertainment, so music buyers are more interested in digging a little deeper" into traditional American music, Barney said.

Welcome to the Muppet Central Forum!

Welcome to the Muppet Central Forum! Jim Henson Idea Man

Jim Henson Idea Man Back to the Rock Season 2

Back to the Rock Season 2 Bear arrives on Disney+

Bear arrives on Disney+ Sam and Friends Book

Sam and Friends Book

! Anyways, being a big jamband fan, I thought it was especially cool that Bela Fleck and the Flecktones grammy is there.

! Anyways, being a big jamband fan, I thought it was especially cool that Bela Fleck and the Flecktones grammy is there.