Super Scooter

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Dec 17, 2002

- Messages

- 6,255

- Reaction score

- 110

Taken from www.usatoday.com on Caroll Spinney's book, The Wisdom of Big Bird:

The bird man of 'Sesame Street'

By Bob Minzesheimer, USA TODAY

SOMEWHERE IN CONNECTICUT — Caroll Spinney doesn't live on Sesame Street; he just works there.

For the past 34 years, Spinney has portrayed both Big Bird and Oscar the Grouch on television's longest-running children's program.

That makes him "the most unknown famous person in America," as he writes in his book, The Wisdom of Big Bird (and the Dark Genius of Oscar the Grouch), released Tuesday. (Related item: Read an excerpt)

The 156-page book (Villard, $16.95) is for adults, not children, but Spinney figures most of his readers will have grown up with Sesame Street, or have children who watch it.

At 69, he says he doesn't mind being unknown and famous. He recalls when a local newspaper published his address and his home became something of a tourist attraction.

"One guy pulled up, honked his horn and yelled, 'Hey, you the bird? Do the voice!' "

Spinney says he felt like telling him, " 'I'm also Oscar the Grouch. So get the **** out of here!' Of course, even Oscar couldn't say that. So I just said, 'Please go away.' "

So let us say that Spinney and his wife, Debra, live in Connecticut and leave it at that. They own 65 acres filled with pines and hemlocks. They designed their home, a 14-room Bavarian-style chalet decorated with antlers from reindeer and caribou. She calls it "our hodgepodge lodge."

Also under construction is their own "folly," what the Irish call something you don't need but want to build. In their case, a stone gatehouse that resembles the ruins of a castle. They call it "Folly Moor Castle."

Spinney is converting a garage into a puppet theater, which comes with a "toy store" filled with gifts for grandchildren and other young visitors. There's a landscaped pond and a roller rink. Some might call it an estate, but not Spinney. "That's too pretentious," he says. He prefers what an 8-year-old grandnephew told him: "You have the best backyard."

Not bad for a puppeteer who spent 10 years performing on Bozo's Big Top on Boston TV, playing Grandma Nellie and Kookie, the boxing kangaroo. The money was good, he says, but the show was "schlock, and I was basically phoning it in. I wanted to do something more meaningful, but I didn't know what."

His break came in 1969, when Jim Henson, of Muppets fame, saw Spinney perform at a puppetry festival in Salt Lake City. He invited him to join an experimental show called Sesame Street, designed to prove that TV can teach children to read and write.

Henson and Frank Oz had created Bert and Ernie but were too busy to spend every day at a TV studio. The set resembled a city street, and they decided they needed more fantasy. Henson thought up two characters that one person could perform — a large bird and a grouch.

Part of the job of being Big Bird is looking the part. Kermit Love, who originally built Big Bird, used to insist, "It's not a costume, it's a puppet." Spinney says it's "actually a brilliant combination of the two."

Big Bird is 8 feet tall, 2 feet taller than Spinney. He holds up his right arm inside the bird's neck. The bird's head is in Spinney's hand. Spinney controls the bird's eyelids and mouth. His left arm operates the bird's left wing and, with a piece of monofilament, his right wing.

Strapped to Spinney's chest is a small TV receiver and wireless microphone. The TV lets Spinney see "the same third-person image that the TV cameras see, not the first-person view that we're all used to seeing to move around."

Spinney says that Henson, who died in 1990, originally thought of Big Bird "as kind of a yokel," and his voice as something like "Mickey Mouse's pal Goofy, or Mortimer Snerd," Edgar Bergen's yokel created as a contrast to his wise-guy character Charlie McCarthy. (Spinney's personal puppet collection includes an original Charlie McCarthy.)

But Henson told Spinney to "go with what I felt came from the puppet. ... Jim liked to work that way. He had faith in his puppeteers, and he had faith in his puppets — the puppet itself often has the power to suggest its character to the puppeteer."

It took most of Sesame Street's first season, but Spinney came to see Big Bird not as the "village idiot," but a curious child. He dropped "the hillbilly accent and made his voice lighter and higher, so that he sounded more childlike. ... He was the too-big kid, much as I had been the too-little kid when I was his age. I suggested that we think of him as a child first learning to read and learning the alphabet, like our audience. That made him about 4½."

As Sesame Street's core audience has gotten younger (dropping from 3 to 5 years old to 2 to 4), Big Bird has aged. "He's about 6," Spinney says, "arrested at 6."

Big Bird's appeal, Spinney says, is that kids think of him as their friend. Spinney goes to great lengths not to be photographed partially in costume, so as not to crush any illusions. A grandson used to phone him and ask if "Big Bird was there." Spinney would talk to him in his Big Bird voice, and his grandson would "tell me his problems and his secrets, what he would never tell his grandfather."

At 10, the boy discovered the truth about Big Bird.

"He was devastated," Spinney says. "He doesn't tell me secrets anymore."

Spinney sees Oscar, with the voice of a cabdriver from the Bronx, as a "paradox." "He gets so much enjoyment out of being miserable," but "he's fundamentally got a heart of gold."

Spinney was 5 when he saw his first puppet and was captivated by the idea that "a whole show could be done with little things on your hands." Three years later at a rummage sale, he bought his first puppet, a monkey with a hole in its head, for a nickel. Soon he was putting on shows for a 2-cent admission. His first show drew 16 people and in 1942, he notes, 32 cents was enough to go to the movies three times.

Life hasn't always been easy. When Spinney quit Boston TV to work on Sesame Street, he took a pay cut and had trouble making ends meet in New York. He almost quit after the first season and writes, "Sometimes you don't recognize what you have is what you always wanted."

His first marriage ended in 1971, which is not mentioned in his book because he says his editor "wanted it to be uplifting, and not confuse things." He describes his whirlwind romance with his second wife, Debra, who was a secretary at Children's Television Workshop, creators of Sesame Street. At the end of their first date in 1974, "we both knew we would be married." He proposed and she accepted 12 days later.

The book also deals with how one of Sesame Street's other puppets, a cute little monster named Elmo, has become its star: "For Big Bird and me, it was like having a new, younger brother in the family. ... I had to get used to sharing the attention."

The show has been widely praised but is not above criticism. In a 1997 book, The Plug-In Drug: Television, Children and the Family, Marie Winn questioned if Sesame Street actually helped children, especially the poor, and suggested it offered "sensory overkill" with commercial-like pacing.

"Why single out this charming, well-produced program for criticism?" Winn asks. Because, she replies, it can lull children into a TV-watching habit.

Spinney agrees that most of TV is not child-friendly. "Overall, I'd say that if you want to preserve your children's innocence, don't let them sit in front of a TV."

He notes that competition from shows such as Nickelodeon's Blue's Clues and new research has prompted changes at Sesame Street, including more uninterrupted time for storytelling.

He says he has no plans to retire. "I'll do it as long as I can hold up the bird's head (which weighs 4½ pounds). I'd love to be doing it 10 years from now. ... There's nothing like a job that lasts."

*****

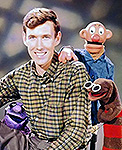

It was accompanied by the picture of Spinney along with a bunch of Big Bird dolls and the Oscar puppet. It can be seen in the reviews section on Muppet Central here: The Wisdom of Big Bird, reviewed.

The bird man of 'Sesame Street'

By Bob Minzesheimer, USA TODAY

SOMEWHERE IN CONNECTICUT — Caroll Spinney doesn't live on Sesame Street; he just works there.

For the past 34 years, Spinney has portrayed both Big Bird and Oscar the Grouch on television's longest-running children's program.

That makes him "the most unknown famous person in America," as he writes in his book, The Wisdom of Big Bird (and the Dark Genius of Oscar the Grouch), released Tuesday. (Related item: Read an excerpt)

The 156-page book (Villard, $16.95) is for adults, not children, but Spinney figures most of his readers will have grown up with Sesame Street, or have children who watch it.

At 69, he says he doesn't mind being unknown and famous. He recalls when a local newspaper published his address and his home became something of a tourist attraction.

"One guy pulled up, honked his horn and yelled, 'Hey, you the bird? Do the voice!' "

Spinney says he felt like telling him, " 'I'm also Oscar the Grouch. So get the **** out of here!' Of course, even Oscar couldn't say that. So I just said, 'Please go away.' "

So let us say that Spinney and his wife, Debra, live in Connecticut and leave it at that. They own 65 acres filled with pines and hemlocks. They designed their home, a 14-room Bavarian-style chalet decorated with antlers from reindeer and caribou. She calls it "our hodgepodge lodge."

Also under construction is their own "folly," what the Irish call something you don't need but want to build. In their case, a stone gatehouse that resembles the ruins of a castle. They call it "Folly Moor Castle."

Spinney is converting a garage into a puppet theater, which comes with a "toy store" filled with gifts for grandchildren and other young visitors. There's a landscaped pond and a roller rink. Some might call it an estate, but not Spinney. "That's too pretentious," he says. He prefers what an 8-year-old grandnephew told him: "You have the best backyard."

Not bad for a puppeteer who spent 10 years performing on Bozo's Big Top on Boston TV, playing Grandma Nellie and Kookie, the boxing kangaroo. The money was good, he says, but the show was "schlock, and I was basically phoning it in. I wanted to do something more meaningful, but I didn't know what."

His break came in 1969, when Jim Henson, of Muppets fame, saw Spinney perform at a puppetry festival in Salt Lake City. He invited him to join an experimental show called Sesame Street, designed to prove that TV can teach children to read and write.

Henson and Frank Oz had created Bert and Ernie but were too busy to spend every day at a TV studio. The set resembled a city street, and they decided they needed more fantasy. Henson thought up two characters that one person could perform — a large bird and a grouch.

Part of the job of being Big Bird is looking the part. Kermit Love, who originally built Big Bird, used to insist, "It's not a costume, it's a puppet." Spinney says it's "actually a brilliant combination of the two."

Big Bird is 8 feet tall, 2 feet taller than Spinney. He holds up his right arm inside the bird's neck. The bird's head is in Spinney's hand. Spinney controls the bird's eyelids and mouth. His left arm operates the bird's left wing and, with a piece of monofilament, his right wing.

Strapped to Spinney's chest is a small TV receiver and wireless microphone. The TV lets Spinney see "the same third-person image that the TV cameras see, not the first-person view that we're all used to seeing to move around."

Spinney says that Henson, who died in 1990, originally thought of Big Bird "as kind of a yokel," and his voice as something like "Mickey Mouse's pal Goofy, or Mortimer Snerd," Edgar Bergen's yokel created as a contrast to his wise-guy character Charlie McCarthy. (Spinney's personal puppet collection includes an original Charlie McCarthy.)

But Henson told Spinney to "go with what I felt came from the puppet. ... Jim liked to work that way. He had faith in his puppeteers, and he had faith in his puppets — the puppet itself often has the power to suggest its character to the puppeteer."

It took most of Sesame Street's first season, but Spinney came to see Big Bird not as the "village idiot," but a curious child. He dropped "the hillbilly accent and made his voice lighter and higher, so that he sounded more childlike. ... He was the too-big kid, much as I had been the too-little kid when I was his age. I suggested that we think of him as a child first learning to read and learning the alphabet, like our audience. That made him about 4½."

As Sesame Street's core audience has gotten younger (dropping from 3 to 5 years old to 2 to 4), Big Bird has aged. "He's about 6," Spinney says, "arrested at 6."

Big Bird's appeal, Spinney says, is that kids think of him as their friend. Spinney goes to great lengths not to be photographed partially in costume, so as not to crush any illusions. A grandson used to phone him and ask if "Big Bird was there." Spinney would talk to him in his Big Bird voice, and his grandson would "tell me his problems and his secrets, what he would never tell his grandfather."

At 10, the boy discovered the truth about Big Bird.

"He was devastated," Spinney says. "He doesn't tell me secrets anymore."

Spinney sees Oscar, with the voice of a cabdriver from the Bronx, as a "paradox." "He gets so much enjoyment out of being miserable," but "he's fundamentally got a heart of gold."

Spinney was 5 when he saw his first puppet and was captivated by the idea that "a whole show could be done with little things on your hands." Three years later at a rummage sale, he bought his first puppet, a monkey with a hole in its head, for a nickel. Soon he was putting on shows for a 2-cent admission. His first show drew 16 people and in 1942, he notes, 32 cents was enough to go to the movies three times.

Life hasn't always been easy. When Spinney quit Boston TV to work on Sesame Street, he took a pay cut and had trouble making ends meet in New York. He almost quit after the first season and writes, "Sometimes you don't recognize what you have is what you always wanted."

His first marriage ended in 1971, which is not mentioned in his book because he says his editor "wanted it to be uplifting, and not confuse things." He describes his whirlwind romance with his second wife, Debra, who was a secretary at Children's Television Workshop, creators of Sesame Street. At the end of their first date in 1974, "we both knew we would be married." He proposed and she accepted 12 days later.

The book also deals with how one of Sesame Street's other puppets, a cute little monster named Elmo, has become its star: "For Big Bird and me, it was like having a new, younger brother in the family. ... I had to get used to sharing the attention."

The show has been widely praised but is not above criticism. In a 1997 book, The Plug-In Drug: Television, Children and the Family, Marie Winn questioned if Sesame Street actually helped children, especially the poor, and suggested it offered "sensory overkill" with commercial-like pacing.

"Why single out this charming, well-produced program for criticism?" Winn asks. Because, she replies, it can lull children into a TV-watching habit.

Spinney agrees that most of TV is not child-friendly. "Overall, I'd say that if you want to preserve your children's innocence, don't let them sit in front of a TV."

He notes that competition from shows such as Nickelodeon's Blue's Clues and new research has prompted changes at Sesame Street, including more uninterrupted time for storytelling.

He says he has no plans to retire. "I'll do it as long as I can hold up the bird's head (which weighs 4½ pounds). I'd love to be doing it 10 years from now. ... There's nothing like a job that lasts."

*****

It was accompanied by the picture of Spinney along with a bunch of Big Bird dolls and the Oscar puppet. It can be seen in the reviews section on Muppet Central here: The Wisdom of Big Bird, reviewed.

Welcome to the Muppet Central Forum!

Welcome to the Muppet Central Forum! Jim Henson Idea Man

Jim Henson Idea Man Back to the Rock Season 2

Back to the Rock Season 2 Bear arrives on Disney+

Bear arrives on Disney+ Sam and Friends Book

Sam and Friends Book